Persuasive design has received a lot of media attention recently. At the end of 2017, before Facebook’s more recent data leak difficulties, a number of high profile Silicon Valley technologists spoke out against the platforms that they helped build. Facebook’s founding president Sean Parker criticised the development of functionality that “exploit[s] a vulnerability in human psychology” in order to “consume as much of your time and conscious attention as possible”. The next day Chamath Palihapitiya, Vice President for User Growth at Facebook until 2011 said he felt “tremendous guilt” for his role in developing interactions that play on “short-term, dopamine-driven feedback loops” to maximise engagement.

I’ve been watching this trend unfold for a while. In 2015, I attended a talk by ex-Google employees Tristan Harris and James Williams (as part of the Bunnyfoot-sponsored UX Oxford speaker series) where they voiced concerns that technology in general, and social media in particular, was working against the best interests of its users by seeking to maximise their ‘time on screen’ for the purposes of advertising.

Since their talk, Tristan and James have been busy. There have been recent articles in The Atlantic, The Huffington Post, and The Guardian, a feature on US documentary series 60 Minutes. Tristan has recently launched The Center for Humane Technology. James won the inaugural Nine Dots Prize last year (with prize money of £100,000 plus a book contract with Cambridge University Press) for an article on how the attention economy is undermining both our individual will and democracy itself.

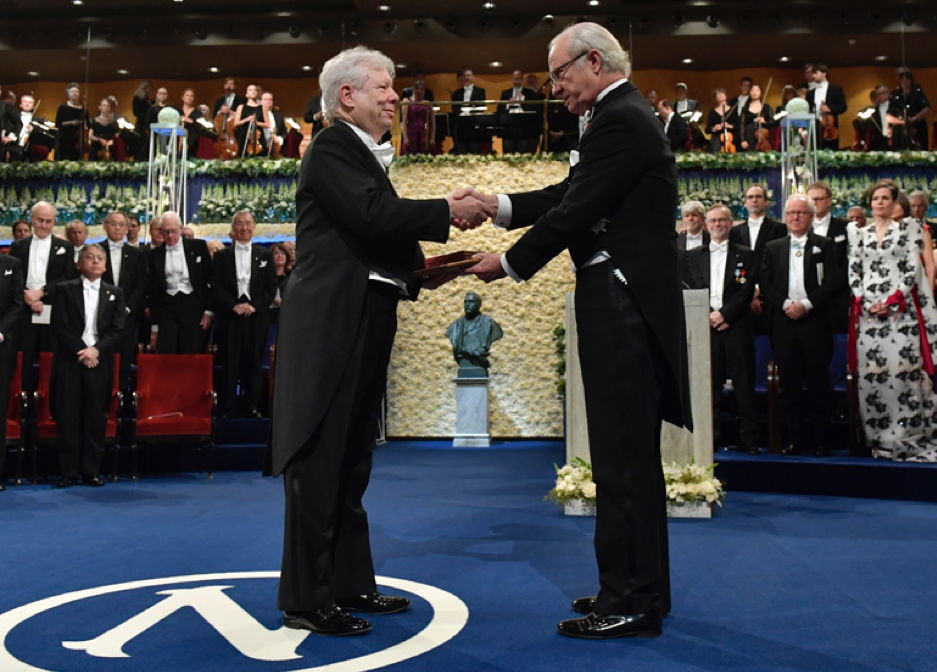

At the same time, in the autumn of 2017, Richard Thaler (co-author of the best-selling book Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness, 2009) was announced as the winner of the Nobel Prize for Economics for his work in persuasive design. Thaler is credited with improving the lives of millions of people through the application of behavioural insights from psychology and the social sciences to government policy. In 2010, Thaler advised Britain’s government as it established the Behavioural Insights Team, otherwise known as the ‘Nudge Unit,’ to introduce persuasive design, or nudge theory, to government policy. For example, understanding that people tend to stick with default settings, in 2012 the UK government changed the previously ‘opted out’ default for company pensions to ‘opted in’. Now automatic enrolment is the ‘new normal’ and has resulted in many people saving for their retirement who otherwise might not have; a clear social good.

Design for persuasion (both online and in government policy) utilises insights into our cognitive biases – our ‘tendencies’ to think and behave in certain ways, often without our conscious awareness. With a background knowledge of these tendencies, designers can produce interfaces or government policies that take advantage of these natural tendencies.

Is this ethical? It all depends on how it is applied.

What Do the Books Say?

Authors of various books on persuasive design argue that it is ethical if it is in service to users’ own goals. For example, most transactional experiences, on and offline, involve two or more parties interacting for their mutual benefit. Persuasive design is, therefore, considered ethical by these authors when it ‘provides an equitable benefit to designer and user’ (Evil by Design, 2013), or if it ‘influences choices in a way that will make choosers better off, as judged by themselves,’ (Nudge, 2009), or if it ‘is in line with the user’s goals’ and improves their lives (Hooked, 2014), and does not ‘persuade people to do something you would not consent to yourself’ (Persuasive Technology, 2002), or when it ‘helps people do what they already want to do’ (Seductive Design, 2011).

In our Designing for Persuasion course here at Bunnyfoot, we also point out that is it much easier (and more ethical) to ‘nudge’ people towards something they already want to do. For example, donations obtained by high street charity fundraisers are frequently cancelled before payment goes out. This is not the case, however, with donations received via charity websites. Both environments contain elements of persuasion, but in the high street people often feel coerced into an action they had not intended to perform, while online they do so in an ‘atmosphere of free choice.’

An Ethical Spectrum

We could consider an ethical spectrum of persuasive design in the following way:

- Designing to Support the User’s Desired Behaviour

This includes behaviour change apps and services that the user willingly engages with in the hope that these are persuasive enough to support their desired behaviour (e.g. sports or weight loss programs). Nudge policies and practices designed to benefit the individuals and society in ways that individuals would themselves choose also fit here. - Aligning the User’s Needs and Business Needs Through Design

Persuasive design that seeks to keep the needs of the user and the business aligned and in balance. For example, a commercial transaction in which a customer wants to find a competent and trustworthy provider and a business that wants to sell its goods or services. - Design that Favours Business Needs Over those of the User

Apps and websites where the interests of the business outweigh those of the user. This may be by design or simply because a business has lost sight of their customers’ perspectives in the face of pressing business objectives. - Deceptive Design

Dark patterns that trick us into purchasing things we didn’t intend to, such as travel insurance or free shipping schemes. Arguably, this should not be considered persuasive design; rather this could be called deceptive design. The distinction here is that the end goal is often hidden from the user in dark patterns.

Sites and services that aim to keep the goals of users and business in balance is the area in which most UX practitioners find themselves working most of the time. UX practitioners help a business maintain this balance by understanding and advocating for their users; we serve our employers by helping them serve their customers. How do we do this? Through user research and an understanding of human psychology.

How Can We Apply This?

Persuasive design patterns are often built upon an understanding of cognitive biases, which behavioural economics and experimental psychology have spent the last fifty years cataloguing. These are tendencies of the human mind to think and evaluate in certain ways, using often unconscious, sometimes emotionally-driven, ‘rule of thumb’ processes. They enable us to make quick decisions, but can also lead us into errors of judgement.

When designing for people, we need to keep in mind that humans are fallible and limited in their assessment of situations and that they are affected by numerous unconscious mental and emotional processes when making decisions. As designers, it’s our job to support this – which means we need to maintain a broader understanding of user-centred design beyond the practice of usability. It reminds us to focus both on how people should do something and also why they should do it. Usability has long been our focus as UX practitioners. We want the world to work better; to be more effective, efficient and satisfying. When we expand our focus to include the emotional and persuasive dimensions of our designs, we do not (or should not) forget the underlying objective of supporting the end user. To guard against losing ourselves in the heady pursuit of persuasion, it’s important to remember that if we intend for the good of the user, the application of persuasive design should be in service of this also.

Let’s take a brief look at the six cognitive biases discussed in Robert Cialdini’s Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, to frame how a focus on persuasion can lead to a better design for both businesses and end users…

Social proof

We tend to follow ‘similar’ others in new or unfamiliar situations. This is why nightclubs make people queue outside and restaurants fill up their seats by the window first. Let us take the example of signing to a new service; for example, the installation of a new smart meter in your home. Once a customer decides to proceed, the online booking process can either facilitate or hinder this. It can encourage or discourage the customer to continue with their intended action. As designers, we would be failing both business and user alike if it was the latter. Embedding social proof to demonstrate that a person’s neighbours are engaged in the same activity can provide valuable social context that decreases anxiety about proceeding. An important caveat to this, however, is that this data must always be true.

Reciprocity

We generally aim to return favours, pay back debts, and treat others as they treat us. This is why my local fudge shop offers free samples to pedestrians passing by. Rather than seeking to induce feelings of indebtedness, this principle should remind UX practitioners to offer something of value first before asking anything of the users of their site or service.

Commitment

People tend to have an internal ‘story’ of who they are and aim to remain consistent to this persona: this is why it can be hard to change someone’s behaviour. However, should you manage to achieve this, you’re likely to find you have them for good! This principle reminds us that people need support when making choices, especially when adopting new behaviours. Offering lower points of entry, such as a ‘save for later’ option as a half-way house to purchase, or a free introductory offer allows people to feel their way in slowly, one step at a time.

Authority

We tend to follow authority and look to leaders and experts for guidance, and as part of this, we look for signs of this authority – which is why policemen, doctors and business people wear uniforms. We want to feel confident that the people we liaise with and who support us are competent in their field. This is why it’s important to support users by demonstrating and signalling your expertise.

Scarcity and Loss-Aversion

Scarcity and loss aversion can be tricky. We tend to value things more when we think they are scarce, and we do not like to lose what we already have, or miss out on what we could have had. This is why accommodation and airline booking websites tell us that there are twelve people currently looking at the room we are considering, or only two seats remaining on a flight. If this information is true, it could be considered informational and helpful. This approach is often intended to induce a fear of missing out in order to nudge the customer towards purchase. This tactic needs to be used wisely and with restraint. The Competition and Markets Authority is currently investigating some booking websites for ‘pressure selling’ using these techniques. Where inducing anxiety may become most ethical however, is at moments where a pause for reflection is necessary to safeguard a person’s well-being.

Likeability

We are more likely to say yes to those we like; this is why salespeople try to build a rapport and why websites use humour and copy with a friendly tone of voice. Extending this further reminds us to expand our focus beyond the merely functional in the pursuit of human relationships.

There are many other principles beyond Caldini’s six categories that make up the design for persuasion toolkit. Many fit just as well in the category of usability; the ‘paradox of choice’ is a well-known principle that choice architects and designers tend to be well aware of. It has been shown that too much choice results in decision paralysis, which is why supermarkets present ten types of jam instead of a hundred. Presenting the optimal number of choices (often fewer, better differentiated choices) increases the likelihood of a decision being made and action being taken. This principle reminds UX practitioners to support choice making by defining an appropriate range of options and providing tools to help manage these options where necessary.

Viewed this way, designing for persuasion is about good design; design that takes the human mind and human behaviour into account for the benefit of those we are designing for. With a commitment to its ethical application, perhaps persuasive design could be relabelled as helpful design, encouraging design, empathic design, or just good old-fashioned user-centred design. A term like ‘empathic design’ positions the UX practitioner as one who fully inhabits the user (emotionally and rationally) in the scenario in which they find themselves and loses the negative connotations that ‘persuasion’ and its synonyms have.

Making the World a Better Place

As we’ve heard from various authors, persuasion is more likely to be ethical when the goals of the persuader are in line with the goals of the user. This is complicated for social media platforms, for example, which have advertising business models. The goals of the users of these platforms are multiple, but they are unlikely to include maximising time on screen for the purpose of advertising.

Silicon Valley has long held aspirations to transform the world for the better, just like their counterculture forebears. With growing concern over the impact of new technology, The New York Times recently reported on a new trend of Silicon Valley executives and engineers attending world-famous retreat centre Esalen as they begin to question their impact on the world. Fifty miles south of Silicon Valley, Esalen is perched atop the beautiful cliffs of Big Sur, California. It has been at the forefront of the human potential movement since the 1960s. Ben Tauber, a former Google product manager, took over as Esalen’s new executive director last summer (much to the concern of some of its longer-term clientele) and is planning programming aimed at top technology executives. Tristan Harris, who we met at the beginning of this article, has already hosted a conference there on internet addiction.

Being interested in human potential and well-being, I have twice visited Esalen. I work in the field of user experience because I like to believe in the power of human-centred design to make the world a better place. Whether it’s the design of systems, services, websites or government policies, an understanding of human psychology favours good design. I practise and teach ‘design for persuasion’ because I see that its insights and methods can be used for good… Which is not to say I don’t recognise that design for persuasion can also be used in negative ways.

In 2011, I undertook a research project to better understand the experience of school children using social media, conducting interviews with groups of 14-year-olds in a South Oxfordshire high school. Their experiences were mixed, ranging from the increased ease of making new social connections and expanding social networks to the snowballing of teenage arguments played out in public, aggravated by the loss of the social cues normally present in face-to-face communication. What motivated my research was a desire to understand whether social media environments could be designed in such a way as to encourage the best in us, individually and collectively. This may not be easy, and current financial models may lack the incentive to pursue this goal, but if we recognise that we are the users of the environments that together we create, and that what we design shapes us in return, we realise the importance of our design choices.

If we follow the golden rule of treating others as we wish ourselves to be treated, we may be guided toward designs that respect our attention, goals and values.

Want to learn more?

- Training course: Designing for Persuasion

- Blog: 12 Ways to Make a Homepage More Persuasive

- Blog: Scarcity in Numbers